- Home

- Rachel Landers

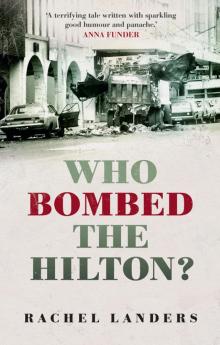

Who bombed the Hilton?

Who bombed the Hilton? Read online

RACHEL LANDERS is a filmmaker with a PhD in history.

Rachel Landers’ Who Bombed the Hilton is a terrifying tale written with sparkling good humour and panache. Landers takes the ‘tatty, fractured saga’ of a horrific terrorist attack in the heart of Sydney, and, backed by remarkable research, she brings it to life. She makes of it a testament to the victims and the investigators, as well as a warning to us in our own age of terror. As we struggle with terrorism, and with the danger of damaging our democracy by our measures to counter it, we do well to remember this story of ‘the one who got away’.

– Anna Funder, author of Stasiland and All That I Am

A NewSouth book

Published by

NewSouth Publishing

University of New South Wales Press Ltd

University of New South Wales

Sydney NSW 2052

AUSTRALIA

newsouthpublishing.com

© Rachel Landers 2016

First published 2016

This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part of this book may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be addressed to the publisher.

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication entry

Author: Landers, Rachel, author.

Title: Who bombed the Hilton? / Rachel Landers.

ISBN: 9781742233512 (paperback)

9781742241470 (ebook)

9781742246413 (ePDF)

Subjects: Ananda Marga (Organisation) – History.

Australian Security Intelligence Organisation – History.

Trials (Conspiracy) – New South Wales.

Judicial error – New South Wales.

Terrorism investigation – Australia.

Australia – Politics and government – 1976–1990.

Dewey Number: 345.94407

Cover design Blue Cork

Cover image The Sydney Hilton on 13 February 1978. The Sydney Morning Herald/Fairfax Syndication.

All reasonable efforts were taken to obtain permission to use copyright material reproduced in this book, but in some cases copyright could not be traced. The author welcomes information in this regard.

Contents

The Hilton and me

The story we tell

The bomb and the bin

Sunday 12 February 1978

Monday 13 February 1978

Tuesday 14 February 1978

Wednesday 15 February 1978

Enter the Ananda Marga

An Australian campaign of terror

Abhiik Kumar

It all goes quiet

‘The blast that shook Australia’

Thursday 16 February 1978

Did the Hare Krishnas do it?

The Bangkok Three

From Scotland Yard to Newtown

February to March 1978

Another bomb

Shadowlands

28 March 1978

A new wave of terror

‘A full-scale terrorist war’

June 1978

The madness of the day

Yagoona

‘Have you ever seen what this stuff can do?’

July 1978

A hardline policy

The immolation of Lynette Phillips

‘Campaigns of violence and intimidation’

A new phenomenon

1979

The locker and the gelignite

The inquest, 1982

May 1983

1989 and after

Epilogue: ‘My heart has been broken’

Note on sources

Notes

Acknowledgments

For D and D

I arrived outside the Hilton only about two minutes after the explosion. Already the air was thick with the noise of sirens and cries from the injured and the peculiar, pungent odour of human blood.

About 15 metres from the rear of the mangled garbage truck where the bomb had exploded I saw what appeared to be the torso of a man covered in a few bloody rags.

Another man was getting up from beside a taxi clutching his face, which had been cut by flying glass from one of the many wrecked shop windows. A young girl was lying behind a car sobbing as the first ambulance screamed to a halt.

Some of the younger State policemen appeared dazed by the shattering event. A more senior Commonwealth officer took control and started moving some youths who had rushed to the scene back down George Street towards the Town Hall.

Ambulancemen and police threw black plastic covers over the human debris.

A team of paramedics began working frantically on one of the police officers who had been caught in the blast. It was hard to recognise him as a policeman. The only distinguishing form was the blue ‘NSW Police’ insignia on his shoulder. Ambulancemen worked feverishly patching a wound at his side and setting up a saline drip.

It was now about 15 minutes since the bomb went off. The area was teeming with uniformed and Special Branch officers, firemen and ambulancemen. A crowd of onlookers was growing rapidly about

100 metres away near the Town Hall. Police also began to move away the handful of journalists who had arrived at the scene.

The first ambulances left for the hospital and the search for clues to the blast was underway.

Peter Logue, AAP, ‘Witness Reminded of Northern Ireland’, Sydney Morning Herald, 14 February 1978.

The Hilton and me

I’m sitting in the Tea Room in Sydney’s Queen Victoria Building across from a man whose name I can’t tell you. Let’s call him Fred. Fred’s a dapper, grey-haired former senior detective in his late sixties who was lionised for his skill in running a series of spectacular covert operations in the 1990s. It has been said that he could wire up an operative and send him into the fray — a drug operation, a dirty cop shop — and they could strip the agent naked if need be and never locate the recording device. Fred is also known for his excessive operational caution. Contact between us was made by a third party and only then were my details forwarded to him. He has asked the waiter to move us to an isolated table and only accepts the third one offered — near an exit, good visibility, away from other diners.

He sits eating his grilled fish with his back to the wall. If I wish to continue contact with him I am to buy him a SIM card and forward it through the third party. While he is, shall we say, assisting me with my inquiries, all this would be a lot more gripping if I was confident he actually had inside information about the bombing of the Hilton Hotel in Sydney at 12.40 am on 13 February 1978 that left three dead and nine wounded. Often described as the first (and, for almost four decades, the only) act of terrorist murder on Australian soil, it is a crime which — despite decades of convoluted trials, inquiries, counter inquiries, commissions, parliamentary declarations and more plot twists than an airport potboiler — remains unsolved.

As Fred and I nibble away at the set lunch menu, he is questioning (head swivelling to check for other diners’ straining ears) why aspects of the security surrounding the inaugural Commonwealth Heads of Government Regional Meeting were so lax. Why were snipers positioned on top of the QVB (he gestures furtively to the right of where we are sitting), yet none of the police stationed across the road, outside the Hilton, were ordered to check garbage bins? The Hilton conspiracy theorists have long pointed to this aberration in what was purportedly standard police protocol as proof positive of the involvement of Australia’s secret service (ASIO) and/or Australian military intelligence and/or New South Wales Special Branch in planting the bomb in the bin themselves. A theory, I find after some robust r

esearch, as fanciful and delicate as a Fabergé egg. Is Fred telling me because he believes it has substance? Or is he testing my agenda? Finding out where my allegiances lie? Does he know something? Or is he just another person tugging at the edges of this tatty, fractured saga? Sad to say, despite my heightened expectations, the latter turns out to be true.

Why is this one crime so absolutely maddening? Australians by nature are not known for their excessive discretion, yet Fred is simply one in a long line of people circling the investigation who are wedded to communicating in opaque coded sentences. Half a dozen leading investigative journalists have sworn only to speak to me off the record, then proceeded to point me towards the same prime suspect — a man who was never questioned by the police. Then they warn me to go no further and recount horror tales of being targeted and harassed. Federal government ministers deny that they authored top secret reports now made public in the National Library under the 30-year rule, despite these reports bearing their names. Malcolm Fraser, the prime minister at the time, told me a few years back that it was a stupid topic to research and instead of wasting my time trying to winnow out the truth of the bombing I should be focusing on the contemporary plight of refugees. Even those individuals suspected of the crime, then allegedly verballed, charged, accused of another crime altogether, jailed then freed, seem committed to joining the chorus of obfuscators. I approach one who says he doesn’t want to talk but sends me his own highly ambiguous autobiography. I contact another who is equally wary but then enthuses about how eager he is to see the finished film.

This is what I am supposed to be doing — researching a treatment for a documentary film. A film in which the story is fast metastasising beyond the tidy narrative trajectories beloved by commissioners at our two public broadcasters. I know — I’ve made a dozen tidy tales for them over the last 10 years. The kind of history documentaries currently in vogue omit the murky and the puzzling or indeed multiple and possibly contradictory versions of what was. One of these commissioners keeps telling me what he wants is a hero’s journey! As if he’s hoping that some manly, handsome secret policeman now in his dotage (perhaps like my lunch partner, Fred) will step forth from the shadows and simplify the whole thing for us and iron out the wrinkles. But this is what history is — it’s a mess. Bits of one event flop into others, things don’t end properly. Witnesses misremember, they evade. They say the car was red when it was blue, the man was dead, the man limped away, the man was a woman.

I retreat into the archives. The truth of this story lies not with the living but with the dead. In bits of papers such as this:

Medical Report upon the examination of the dead body of: Name: UKNOWN MALE believed to be William Favell 36 …

The body was in bits and pieces brought in plastic bags …There was singed hair at certain areas showing it was the head and brief[s] noted that it was a groin. The parts were badly shattered with hardly any bone left intact. Embedded in the body were large amounts of foreign matter such as cigarette butts, labels etc. There was also shrapnel, glass splinters and paint. Cause of Death: Multiple Injuries. Antecedent Causes: EXPLOSION.1

Favell, a garbage collector, was collected from the asphalt on George Street in plastic bags. He had a seven-year-old daughter.

When I first enter the New South Wales State Records building, it’s strangely intoxicating to come across stark reminders of what actually occurred. The Hilton bombing records are unique in Australia. In 1995, in order to placate various politicians on the left and the right who were making fervent calls2 for a joint state–federal inquiry into the Hilton bombing along with the conspiracy claims (fuelled in part by a 1995 ABC documentary called Conspiracy, which you can catch on YouTube), New South Wales Premier Bob Carr and Prime Minister Paul Keating agreed to open the files relating to the Hilton bombing to the public. They have sat in the New South Wales State Records ever since.

Housed in a paddock on the fringe of the city, the archives building looks like a set from a sci-fi movie. It’s hard to get a sense of the physical dimensions of the holdings as only one folder is released at a time, and the catalogue descriptions give a poor indication of what is going to emerge from the Tardis-like vault behind the reception counter. A request for a promising item may only result in a slim manila folder containing time sheets. Another innocuous-sounding listing emerges as a large box stuffed full of revelations. By my estimate the Hilton archive is larger than a walk-in wardrobe and smaller than a two-bedroom house.

This book is the story of my journey through that archive, supplemented by research in many other primary archival sources in Australia and overseas, to find answers.

What I found surprised me.

I was a schoolgirl in Sydney when the bomb went off and I remember exactly where I was when I learnt what had happened. Our teacher, Mrs K, an overly dramatic, skinny woman with a penchant for stiletto heels, recounted the ghastly news and made us bow our heads in a minute’s silence. Things seemed very serious and a girl in my class burst into noisy tears, sputtering that her uncle had known one of the deceased. Despite the clarity of that memory, I, like most people who remember the actual bombing, couldn’t really explain what had happened in the years that followed or, indeed, who did or didn’t do it. It strikes me as odd that such a key moment in Australia’s history is so unexplored. If you’re too young to have any recollection of the bombing it must be intriguing why such a colossal crime remains unsolved and so saturated in conspiracy theories.

After trekking through the evidence available, it is clear that most of the answers lie in the first 12 months after the bombing. After that, the narrative becomes hijacked by a miscarriage of justice story — a story taken up by activists and an emerging new generation of journalists and papers like Nation Review and the National Times. This is the story people remember, but it tends to obscure the truth. It’s a story that was very much of its time — a sort of impassioned tale of the late 1970s, following in the wake of the anti-Vietnam War sentiment early in the decade and the rage around the dismissal of the Whitlam Government in 1975. It’s a story that lives in the public domain as the goodies — counter-culturists, the free press, anti-authoritarian citizens — versus the baddies — the police, the secret services, politicians, institutions. It’s also a narrative arc that Australians adore, that of the underdog fighting for truth and justice and triumphing. The thing is, this story tells you nothing about who might have planted a bomb outside the Hilton Hotel that February night.

The story we tell

The public story goes like this:

13 February 1978. There is a gathering of regional Commonwealth heads of state (CHOGRM) at the Hilton Hotel. This includes leaders from Tonga, Nauru, Singapore and India. Early in the morning, before the summit opens, a bomb goes off when a bin outside the George Street entrance is emptied into a garbage truck. Two garbagemen, Alec Carter and William Favell, are killed, and a policeman, Paul Burmistriw, is badly injured. He will die nine days later. Inside there is pandemonium. Prime Minister Fraser calls out the Army to protect the foreign leaders.

By morning a task force of over 100 is assembled to catch the bomber. In this team are 58 detectives, 15 of whom are experienced homicide investigators.1The Premier and the Prime Minister offer a reward of $100 000. Suspects start to be brought in for questioning, including the feminists and anarchists who had been protesting during the arrival of various leaders the day before. Members of the religious sect the Ananda Marga are also questioned — they are alleged to have been behind attacks on Indian nationals in Australia over the previous six months in protest at India’s imprisonment of their leader, Baba. It is thought that India’s Prime Minister Desai, who was staying at the Hilton, could have been a target. The Ananda Marga public relations secretary, Tim Anderson, immediately refutes these suspicions in a press conference, stating that the sect is shocked by the bombing and extending the sect members’ sympathy to the families of the dead and injured.

The Australian wing

of the Indian-based Ananda Marga is made up of a few hundred followers. They practise yoga, meditation, run their own schools and soup kitchens and raise money for disaster relief.

Within days the investigation appears to have ground to a halt. There are repeated newspaper articles reporting a lack of leads, dead ends and appeals for information from the public. Simultaneously, various individuals make claims about it being an elaborate plot hatched by ASIO, military intelligence and New South Wales Police Special Branch (the police charged with looking after VIPs) in order to scuttle any ongoing investigations critical to their practices and justify their respective futures.

Months crawl by — the papers keep up their rattat-tat of gloom — no new leads and no evidence.

15 June 1978. Three young members of the Ananda Marga sect are arrested: Tim Anderson, 26; Ross Dunn, 24; and Paul Alister, 22. The police say they have caught Dunn and Alister with explosives in a car at Yagoona in south-western Sydney as they were attempting to blow up Robert Cameron, the leader of the Nazi National Alliance. According to the police, Anderson was caught with incriminating evidence at the sect’s headquarters in Newtown. All three confess that night to conspiracy to murder Cameron. One of the arresting officers is Roger Rogerson.

July 1978. A few weeks after the arrests it transpires that a man named Richard Seary was with Dunn and Alister the night they were arrested. Seary had been posing as a sect member but was in fact working as an informant for New South Wales Special Branch and had tipped off the cops about the Cameron conspiracy. Seary then thickens the plot by adding (two weeks after the event) that, en route to Yagoona, Dunn and Alister admitted they had committed the Hilton bombing.

Anderson, Dunn and Alister say that the police have planted the evidence — explosives and incriminating letters — and have physically assaulted them and fabricated the confessions. They say Richard Seary is a liar and a fantasist.

Who bombed the Hilton?

Who bombed the Hilton?